Introduction to Miniscript

Introduction

In this article, we will discuss Miniscript, aiming to cover the main ideas, which we believe are of interest to anyone looking to start using this powerful tool.

The best way to get introduced to a new technology is, as we know, by reading its documentation. The most comprehensive documentation can be found at: https://bitcoin.sipa.be/miniscript/, written by Pieter Wuille, one of the creators of Miniscript. There, we find the definition that we will use in this article:

Therefore, according to the definition, Miniscript is:

First, we will begin by discussing some of the concepts that appear in the definition.

Bitcoin Script

If a currency is to be of any use, it is necessary for it to be transferable.

Therefore, it is necessary to define a mechanism that allows such transfer. Additionally, such a mechanism must be able to ensure the fulfillment of certain conditions, for example, that the person transferring the currency has the right to do so.

In the case of Bitcoin, the language that allows defining (and checking) these conditions is known as Bitcoin Script.

Bitcoin Script is a relatively simple programming language but, as we will see, can be difficult to use in practice.

In the following sections, whenever we use the word script, we will be referring to a Bitcoin Script.

Structure

Every language implies structure, and the structure of Miniscript, as the definition tells us, enables among other things:

- Analysis

- Composition

Analysis

Analysis is the act of examining something in detail, in this case, a script.

Some of the analyses that Miniscript facilitates are:

- Analysis of spending conditions: What are the spending conditions of a script?

- Security analysis: Is it possible for a script to be malleable?

- Cost analysis: What will be the cost of using a script?

Composition

Composition is the act of joining two or more things to form a new one.

In the case of Miniscript, composition refers to the ability to join two or more fragments (scripts) to form a new one.

Subset

For better or worse, the word subset brings with it an intuitive connotation, and like all intuition, it is not always correct. One example will suffice:

While it is true that the set of liquids has much more to offer than just water, it's easy to see why, in our daily lives, we are only interested in a particular subset.

The same is true in the case of Miniscript: the selected subset is such that it allows us to work with Bitcoin Script without having to worry too much about some of its complexities.

Although the above comment may seem trivial, it actually encapsulates the main motivation for using Miniscript:

In particular, with Bitcoin Script, it is difficult to perform the analyses mentioned in the previous section, namely:

- Determine if a script is correct.

- Determine if a script is safe (not prone to being malleable).

- Estimate fees (the size of a transaction in the worst case).

Before we continue our discussion, it is useful to introduce the following definition:

Spending condition: is the set of minimum conditions that, when met, allow a UTXO to be successfully used in a transaction.

For example:

- The (single) spending condition of a single-sig wallet is the owner's signature.

- The (single) spending condition of a 2 of 2 multisig wallet is the signature of the two keys involved.

- One (of two total) spending condition of a 1 of 2 multisig wallet is the signature of one of the keys involved.

While some points, like security, can (and often are) minimized by policy-level restrictions, Miniscript also solves another problem:

The answer is, for most of us: No.

To convince ourselves, let's look at the following example:

Miniscript Policy (A):

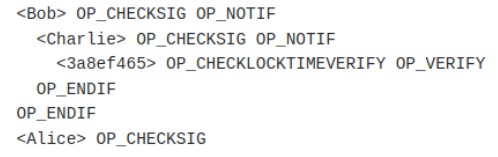

Bitcoin Script (B):

We invite the reader to analyze expression (A) for a moment.

Assuming that a condition is a spending condition, in the context of Miniscript, if the entire expression, when logically evaluated, becomes true, it should be easy to convince oneself that the spending conditions are:

- Alice's signature and Bob's signature

- Alice's signature and Charlie's signature

- Alice's signature and the specified time (1710526010 unix time) has elapsed.

If the spending conditions mentioned above are true, it follows that:

-

The and and or operators behave similarly to their logical counterparts (when in doubt, consult the truth tables for conjunctions and disjunctions).

-

Each of its elements must be able to be evaluated to a boolean (true or false).

It would be incorrect to claim that expressions (A) and (B) are equivalent (remember our brief digression on subsets), but the spending conditions expressed in Miniscript are preserved when transitioning (with the help of a compiler) from (A) to (B).

Two Miniscripts?

The reader may have noticed that in the previous section we referred to expression (A) as Miniscript Policy and not as Miniscript.

The reason is that they are two different languages.

The following expression (C):

Is the Miniscript generated by the Miniscript Policy (A).

Let's examine (A) again:

Notice that the expressions are very similar, only some things are removed from (A), like that strange ‘9@’ (which we will talk about in the next section), others are added like the ‘v:’, and to the ‘and’ and ‘or’ a couple of characters are added (in reality, these are types and modifiers).

While we will not go into details about what each of the changes that occur when going from (A) to (C) means, it is worth mentioning how this transformation occurs:

The Miniscript (C) is obtained by compiling the Miniscript Policy (A).

Naturally, the reader might think that the reason for these two languages to exist is only to save us the work of adding all those characters (apparently necessary) that appear in (A), but the reason turns out to be more fundamental:

To illustrate the problem, let's take a simple spending condition.

pk(A) is true if there is a valid signature from A and false otherwise.

In principle there are at least four ways (opcodes) to check this condition:

- OP_CHECKSIG

- OP_CHECKSIGVERIFY

- OP_CHECKMULTISIG

- OP_CHECKMULTISIGVERIFY

In fact, it is enough to realize that there are many ways to combine the 'and' and 'or' operators to express a given condition.

If there are several options available, we have the freedom to choose certain parameters of interest to facilitate the choice, one of them, which we will discuss next, is:

Probabilities and Optimization

Previously we mentioned that to determine the spending conditions it is useful to think that all the elements within the 'and' and 'or' operators must be able to be evaluated to a boolean. If we assume that pk(A) is true when there is a valid signature from A and false otherwise, the question arises:

What does ‘N@pk(A)’ mean where N is an integer?

Let's start by clarifying that ‘N@’ is NOT an operator on the boolean pk(A):

N@pk(A) is true if pk(A) is true and false if pk(A) is false, regardless of the value of N.

‘N@pk(A)’ is the notation for assigning pk(A) a relative probability compared to the other conditions that appear within the same ‘or’.

Therefore, in expression (A), the presence of ‘9@pk(Charlie)’ is to communicate to the compiler that the condition ‘pk(Charlie)’ is 9 times more likely than the condition 'after(1710526010)'.

But, what is the purpose of assigning probabilities?

As mentioned in the previous section, given a set of possible choices, it is to our advantage to choose the one that, among other things, is optimal.

We say a choice is optimal if, by including it, the resulting script's size is the smallest.

By assigning probabilities, we can communicate to the compiler that one branch is more likely (or not) than the others; in other words, we tell it to prioritize optimizing (reducing the size) of the more likely branch, at the expense of possibly increasing the size of the less probable one.

Conclusion

In this article, we have talked a bit about the motivation to use Miniscript, as well as some of its main ideas. We invite the reader to read the official documentation if interested in a more in depth discussion.

In subsequent publications, we will discuss Taproot and how it can be used in conjunction with Miniscript.

Author:

Armando Medina